At a high level, the Jamstack is an architectural approach to web apps that focuses on:

- generating cacheable, static assets at build time whenever possible,

- deploying those assets to CDNs, and

- using client-side JavaScript to call third-party APIs and serverless functions for dynamic interactions and data.

For individual developers, the Jamstack lowers the barrier to entry, cuts down on the number of tools to learn, and provides modern tooling to build web apps.

For teams, the Jamstack helps enforce a more maintainable architecture and decreases iteration time, enabling faster delivery along with increased security and scalability.

For users, Jamstack apps typically load faster and are more reliable, which makes the web a less frustrating place.

The Jamstack is not a traditional tech stack.

The Jamstack is not a “stack” in the same way the term is commonly used, such as the LAMP stack (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP) or MERN stack (Mongo, Express, React, Node).

It is true that the origin of Jamstack comes from the acronym JAM, standing for JavaScript, APIs, and Markup (or maybe Markdown? who knows?). However, as people started adopting the principals of Jamstack, it immediately outgrew this stack and came to represent a more generalized approach.

Instead of being a descriptive acronym describing a particular tech stack, Jamstack joins “radar” and “laser” as an often-inaccurately-used acronym that represents a general idea instead of a precise origin.

Jamstack is more of an architecture.

The Jamstack is similar to terms like “microservices“ and “monolith“ because it doesn’t describe the specifics of implementation. Instead, these terms communicate the high-level details about how the code is organized.

If we hear someone describe a codebase as a monolith or microservices, we get a broad idea of the architecture and can make some high-level assumptions about how the code works. However, knowing the high-level architecture doesn’t tell us anything about the specifics of how the code is implemented.

Jamstack is like that: if we hear an app described as a Jamstack app, we can make broad architectural assumptions, but the implementation details can vary widely between teams.

What architectural decisions make an app a Jamstack app?

If the Jamstack allows us to make architectural assumptions, what are those assumptions? In the broadest strokes, the software architecture decisions that make up the Jamstack are:

- Assets are generated at build time, not request time.

- Apps are deployed to CDNs instead of always-on servers.

- Deployments ship atomic, static assets instead of dynamic, derived assets.

- Dynamic interactions use APIs and serverless functions instead of monolithic servers.

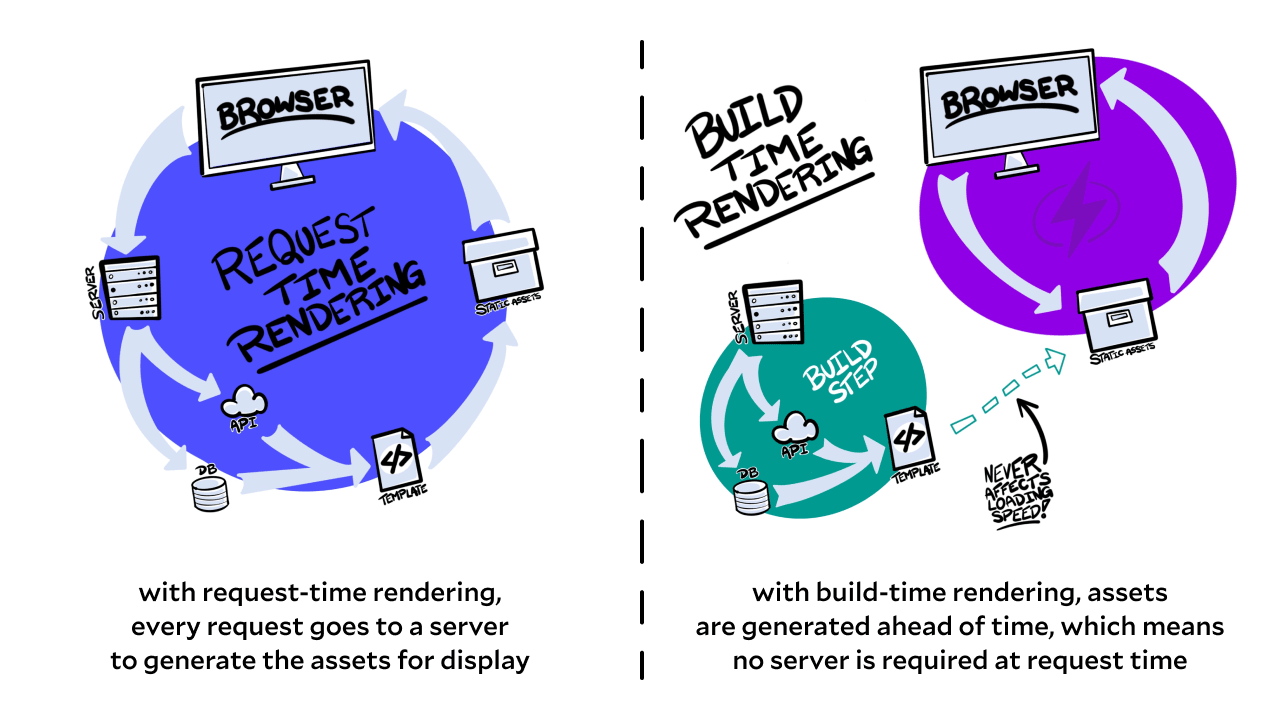

Assets are generated at build time, not request time

Any performance-minded developer will tell you to cache responses to both speed up our apps and reduce load on our servers. In just about any production stack out there, we can expect to find caching in place.

Often, this is done by waiting for a site visitor to hit a URL, doing work on the server at request time to generate the assets required to render the page, then caching that response so the next visitor is able to get the assets without waiting for the server to do the work.

The Jamstack takes this one step further: if you generate the cache at build time, no one ever has to wait for assets to be generated.

This gives us much more certainty about our deployment process because, as Phil Hawksworth puts it, “by pre-rendering our sites we can be certain that our pages are correct before we deploy them”.

Apps are deployed to CDNs instead of always-on servers

By thinking of our apps as pre-generated caches, we eliminate the need for always-on servers. This creates several huge benefits:

- Our sites load faster because we can deploy to Content Delivery Networks (CDNs), putting our app assets closer to the people trying to load them.

- We cut down on costs. Using CDNs means we don’t have to pay for massively scalable servers to handle traffic spikes. We’re shipping more reliable sites and reducing operational overhead.

- Our apps are more secure because there’s no active connection to a server or database. Sites are made of pre-generated, static assets, which means we don’t need a server or database to display them.

- Our apps are more stable. There are very few moving parts between your site visitors and the content they’re requesting, so there are fewer points of failure in the request chain.

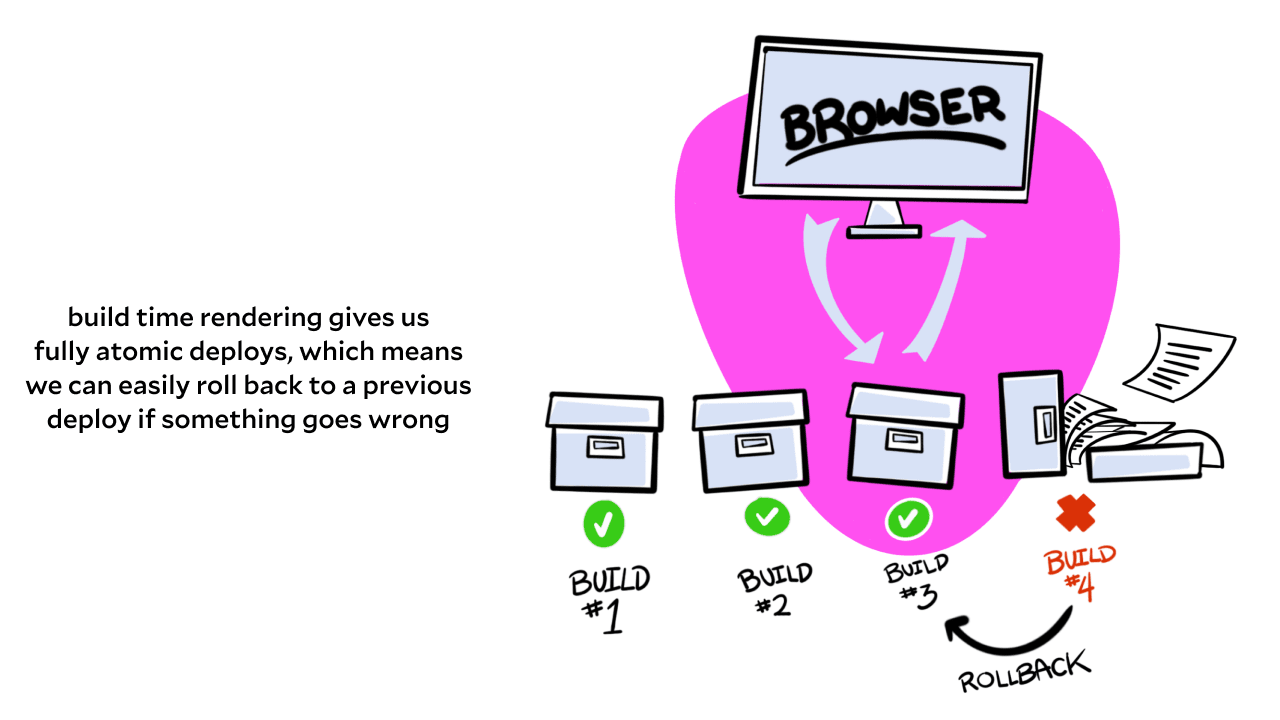

Deployments ship atomic, static assets instead of dynamic, derived assets

Because we build the entire site once, we get a very cool benefit: atomic deploys. Once the site is built, we have all of the markup, styles, scripts, data — everything in one place that won’t be modified again after the build. This means that if we make a mistake, we can roll back to a previous deploy by straight-up replacing the bad deploy’s files with a previous good deploy.

This also means we can set up previews for new ideas quickly and easily: we can create a branch in our repo, run a build, and then host that site at a private, temporary URL to send the idea around for feedback.

At Netlify, where I work, instant rollbacks, branch deploys, and deploy previews for pull requests are all powered by this concept. I rarely hear anyone talk about it, but this is one of the most powerful benefits of the Jamstack.

Dynamic data uses APIs and serverless functions instead of monolithic servers

Not everything can be cached, however: what if our site’s users log in and need to see their own data? It doesn’t make sense to try and build that ahead of time — it would be a huge security risk, for one thing — so we still need a way to handle user input and load personalized data on-demand.

Handling dynamic data and interactions is a core part of the Jamstack approach, which may seem counterintuitive after we’ve just spent most of this article talking about generating static assets.

This is an important distinction: static assets do not mean static apps.

A JavaScript file is a static asset. Using JavaScript, we can make calls out to other APIs, third-party services, and all sorts of other data sources — this means we have all the same flexibility to generate dynamic content that we have with a traditional server request.

The benefit here is that we get to focus just on the data and business logic instead of building out all the boilerplate for a service and dealing with the operational overhead of keeping it deployed and maintained.

Isn’t this the same as what we used to do?

In a sense, the Jamstack is a return to a very old method of building websites: we create a static asset — an HTML file — and put that online somewhere. If you’ve ever dragged a file into an FTP program to make website changes, this may feel familiar.

The difficulty of manually editing every file on a site and uploading the changes via FTP was high, and it left a lot of room for human error.

As web development evolved, more tooling was created to generate assets automatically. We saw the rise of PHP, followed by the even more dramatic rise of WordPress. We saw Node enter the scene, with frameworks like Express for building our own template-driven servers. We saw Grunt, Gulp, Webpack, and other tools enter the mix to automate complicated build processes.

And somewhere along the way, it became complicated to get a website up on the web.

Jamstack returns to the old way of deploying static files as a folder — we’re swapping out traditional hosting for a CDN — and introduces new innovations that make the process of creating sites boring again.

The Jamstack combines tried-and-true development and deployment strategies with more ergonomic tooling, better abstractions around common infrastructure, and improvements to the JavaScript ecosystem have helped smooth out the developer experience around all this powerful tooling, decreasing the friction to build and deploy web apps.

The Jamstack is not just marketing fluff.

A common criticism of the Jamstack is that it’s just a marketing term for stuff that already exists.

Depending on what you’re predisposed to believe, this statement can fall anywhere on the spectrum of true and false.

Put cynically, the Jamstack is “just putting static files on S3”.

Put charitably, the Jamstack is “revolutionizing web development by removing barriers and giving frontend developers superpowers”.

Somewhere in the middle lies a more objective assessment: the Jamstack is a label for a broad assortment of website-building techniques. These techniques are based on several mature solutions that have existed long before the Jamstack was around to describe it, and also introduces new innovations that streamline the process and make building in this way more approachable.

The Jamstack is dope.

To recap, let’s run through the Big Ideas™ of the Jamstack that we covered in this article:

- The Jamstack is not just marketing fluff.

- The Jamstack is not actually a tech stack.

- The Jamstack is an architectural approach to building web apps that focuses on static assets shipped to CDNs using APIs and/or serverless functions to add dynamic functoinality.

- For a large number of web apps, the Jamstack will be faster, more reliable, and more efficient than other architectural approaches.

I’m obviously biased, given that I work at Netlify. However, I love the Jamstack and have been recommending it since long before I took a job at Netlify — I was pushing for this approach when I worked at IBM back in 2016 and didn’t have a word to describe the approach yet. 💜

Are you exploring the Jamstack for an upcoming project? What questions do you have about it? I really want to hear from you — hit me up on Twitter or reply to any of my newsletter messages! (I’m serious, too: hearing what you find confusing, inspiring, frustrating, etc. about the Jamstack helps me know what I should create content about, so please don’t hold back!)